Blue Lagoon (1988). Acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of Oeno Gallery.

Blue Lagoon (1988). Acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of Oeno Gallery.

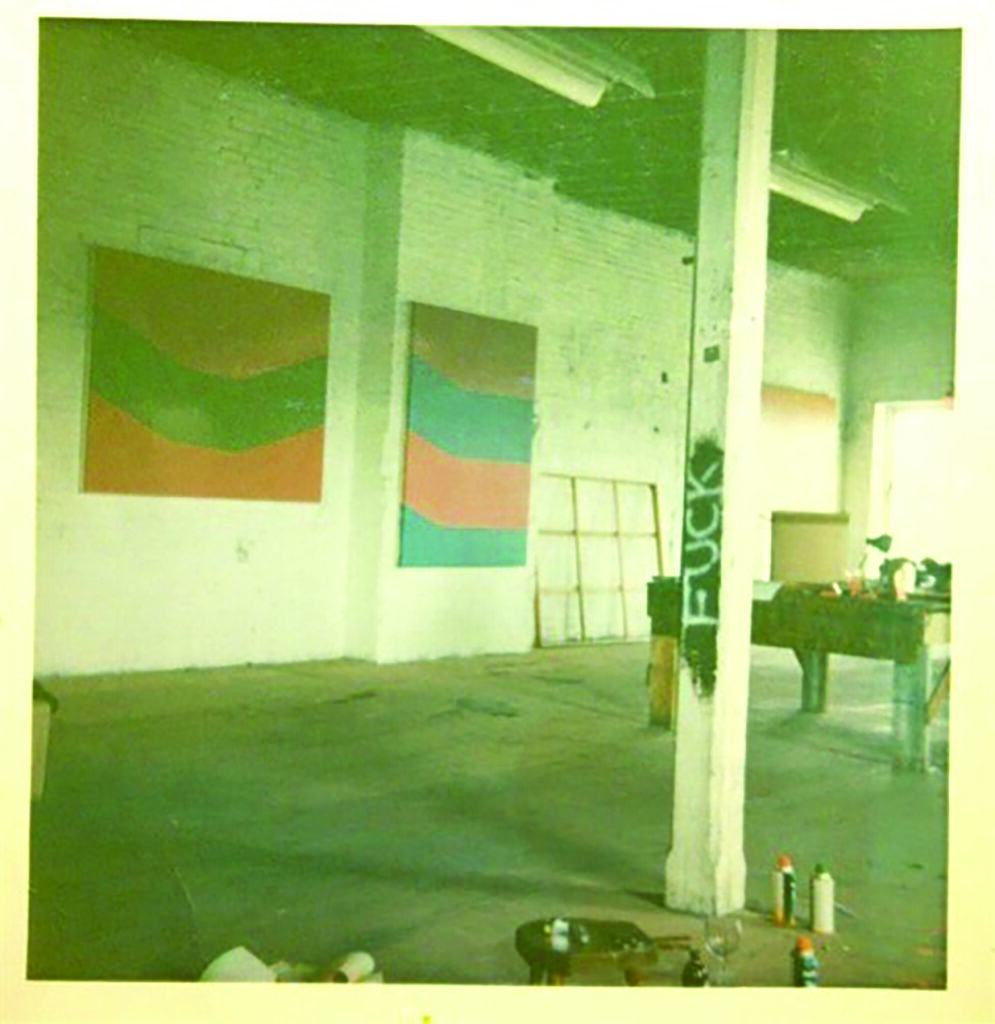

The focus of national attention in the 1960s, when she was in her twenties. Confidently producing massive, striking “colour form” canvases, singing with the energy of vivid colour colliding. Sharing a studio with Jack Bush, who championed her work. And yet. When a singularly accomplished series of “Highway Paintings,” evoking the experience of driving the newly opened 401, was turned down by Carmen Lamanna, owner of a key gallery in the Toronto art scene of 1969, she rolled them up and hid them away.

For fifty years.

A few years later, in 1976, Milly Ristvedt moved from the centres of Toronto and Montreal to Tamworth, somewhere north of Napanee. A stunning early career filled with exhibitions started slowly to quiet. At least on the outside. But Ristvedt was painting, obsessively, intensely, personally. Experimenting over decades. And stowing the canvases safely away.

This trove was discovered by Oeno Gallery owner Carlyn Moulton in 2017. Prompted by a chance introduction, she and her team visited Ristvedt’s Tamworth studio. They unrolled hundreds of canvases, stunned by what they were seeing. Moulton immediately took charge, sketching out to Ristvedt how Oeno Gallery would represent her.

A 2021 exhibition of the Highway Paintings brought national attention once again.

In these early works, bold, geometric strips of colour reassemble the experience of being driven down a highway, the only highway for most Ontarians, the 401, and looking out the window at a landscape robbed of its full presence. So immersive are they, the viewer doesn’t just see — though there is a shock of recognition, the colours are asphalt and yellow and brown and green — but re-experiences the straight lines of the road, jumbled by both perspective and by memory. The hard-edged, geometric shapes, which contain and direct and control the colour, evoke disembodied hurtling. Lines are the dominant force, but there is no sense of intersection — they only run up against each other. The highway directs your path and the speed at which it must be taken. We are all helpless on it.

The very fact that we are willing to subject ourselves to it, however, is a form of hope. Of energy. As is the way the paintings help us to make sense of our experience. They reassemble what we know but do not know.

After that 2021 exhibition, one of Ristvedt’s Highway Paintings was acquired by the National Gallery of Canada, which also purchased the shaped colour form canvas, Joyride (1968). A third acquisition was April Sunny Day, painted 20 years later, in the late 1980s, the artist at the top of her powers. She had long since moved from hard edges to gestural works full of beautiful colour, a shift one critic locates to the move from city to country.

In the gestural works, however, time is still of the essence. As is control.

Ristvedt works through a technique called “wet-on-wet.” She spends perhaps a week sketching out ideas and assembling every possible colour and implement she might need. When the day comes, everything must be done while the fast-drying acrylic paint is still wet. A colour background is applied, and on top of that a series of other colours, which move and bleed. Much of the work is in managing the shapes of the colours, how they work together. One of these paintings might take two hours. At the most.

Painting is my freedom ‘to be’ in the world, to transform what I think and feel about life,

— Milly Ristvedt

to express the essence of things that matter.

Colour

is the

magical sensation and substance, the ‘philosopher’s stone,’ that for me

represents hope in a time of great challenge for us all.

“Once you apply paint to a canvas,” says Ristvedt, “the canvas takes over. Cohesion, the sense of the whole, is what you must answer to. You have no control anymore.”

Across Ristvedt’s work, colour creates a conversation with the viewer. It is as though her paintings are speaking a language one doesn’t fully understand. We can feel its force, but it is not clear what is being said. The way the paintings ask us to move between and within their colours suggests finding a place in one’s mind that evades words, or that moves between them. “A painting is a conversation. It invites you to look again, take another moment,” she says. “Isn’t that just the nature of seduction? Asking you to look again?”

The colours — deep and vivid and rich, created through layer after layer of paint – draw on shared memories and associations. For me, they evoke the glimmering of thought, stretched out on a fretwork of feeling, and its frustrating momentariness, which is also its beauty.

For others, the right metaphor is music. Sky for a Roof (2019), which Ristvedt painted while the saxophonist David Mott played. “I had the pleasure of performing a ‘duet’ with Milly for an audience as she painted,” recalls Mott. “There was no hesitation or wavering in how she placed the brush strokes on the canvas. Her mastery is undaunted by circumstances. She was free to paint with complete conviction while observed by others.”

Shaping Colour launches Saturday 6 September at Oeno from 2-4pm. The artist will give a talk at 3pm.

See it in the newspaper